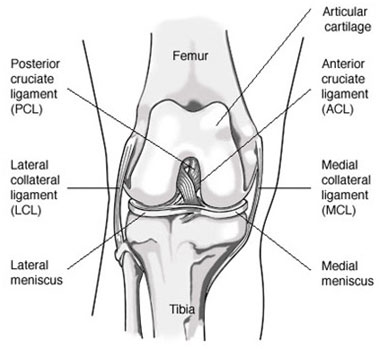

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is a main stabilizer of the knee. It keeps the tibia (shin bone) from moving forward on the femur (thigh bone) and also helps to prevent rotation between the two bones. The ACL is essential for normal knee function in aggressive running, cutting, and jumping-type activities. It is less important for straight ahead activity.

Associated Injuries

Often, other structures in the knee are injured when the ACL is torn. Which structures are injured and to what degree influences the treatment and long-term prognosis for your knee.

- Bone bruises are present in 60-80% of ACL tears. They can cause a significant amount of pain on their own. This is worse with weight-bearing and may be a reason to use crutches.

- Meniscal tears are often associated with ACL injuries. These can occur at the same time as the ACL injury or from a separate instability episode after the ACL was torn.

- The articular cartilage can also be damaged at the time of an ACL injury or from another instability episode.

- Occasionally, one of the other ligaments of the knee is injured with the ACL. This makes the knee even less stable. It also can affect the timing of any surgery, how much surgery we recommend, and the rehabilitation after surgery.

Diagnosis

History and Physical Exam

Your provider will discuss your symptoms with you, including their onset, details of how you hurt your knee, and any pertinent past injuries or surgery. Examining both the normal and injured limbs is also critical to hone in on the correct diagnosis.

X-Rays

X-rays of your knee are an important part of the evaluation if we suspect an ACL tear. They allow us to look for fractures, arthritis, alignment issues, and injuries to the growth plate in younger athletes.

MRI

A Magnetic Resonance Image (MRI) is different from an x-ray because it allows us to see the soft tissues (cartilage, ligaments, and meniscus) around the knee. It also takes longer than an x-ray and can be troublesome for people who are claustrophobic. An MRI will help to confirm the ACL tear and look for associated injuries.

Treatment

The goal of treatment for an ACL tear is to decrease pain and restore function and stability to the knee. The treatment recommended by your doctor will depend on your age, the sports and activities you do, and the presence of other injuries.

There are two global approaches for treating ACL tears:

- 01. Non-operative management (no surgery). For patients who have no other injuries, it is possible to do aggressive physical therapy to strengthen the hamstring muscles and help stabilize the tibia. Bracing to stabilize the knee and permanent modification of your activities to minimize the chances of recurrent instability and demands on the knee are also essential. This option is often chosen for less active or older athletes, but it shouldn’t be discounted. This treatment can have excellent long-term results in the right patients.

- 02. Surgery:If the ACL ligament itself is torn; it does not generally heal on its own. We know that having an ACL tear increases the risk of developing cartilage damage and arthritis in young, active people. With each subsequent episode of instability or “giving way”, the chances of damaging the menisci and articular cartilage increase. The idea behind ACL surgery is to stabilize your knee and thereby decrease the number of instability episodes and minimize further damage to the meniscus and articular cartilage. It is important to understand that ACL surgery will not reverse or cure existing cartilage damage or arthritis, however.

There are two types of surgery that can be done for ACL tears:

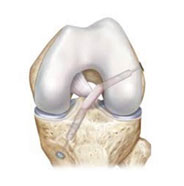

- Primarily ACL REPAIR: Occasionally (about 10% of the time) the actual ACL ligament tissue is left essentially intact, and just pulls off its femoral attachment. If this happens, we are sometimes able to arthroscopically re-attach (repair) the ACL back to the femur. Recovery from this surgery is accelerated as compared to a traditional ACL Reconstruction. Results are good to excellent in the right patients, but the tear pattern has to be just right to allow for successful repair. Often an MRI can suggest if a tear has the potential to be repaired, but we can almost never confirm this for sure until we can look at and manipulate the tissue at the time of surgery. If we find that the tissue is too damaged to allow for primary repair, then we proceed with an ACL reconstruction (see below) during the same procedure.

- ACL Reconstruction: This is generally our recommendation for younger patients and people who want to continue playing sports, and for those patients where ACL repair is not an option. Reconstruction is done for about 90% of ACL tear patients. If the tissue isn’t repairable, then we must reconstruct it (replace it with another tissue) in order to successfully stabilize the knee. In order to do this we need to take graft tissue from another source, either your own tissue (called autograft) or donated (cadaver) tissue (called allograft). In all cases, the graft undergoes a period of healing and remodeling to function like a ligament over time. Because of this healing time, protecting your graft for some time after surgery is important and will direct your rehabilitation. See the separate section on Graft Choices below.

ACL surgery is a significant undertaking and the physical therapy afterwards is extensive. This surgery is not generally needed to regain normal function in life’s daily activities or straight-line activities. It is often needed for participation in pivoting or cutting sports however, including skiing and snowboarding.

Pre-Operative Rehabilitation

ACL surgery should be done after the initial injury has had time to settle down. This decreases the risk of stiffness after surgery.Your knee should not be swollen, you should havefull range of motion, and you should be able to walk normally. There are some exceptions to this; sometimes an associated injurylike a large meniscal tear which blocks full knee motion, multiple ligament injuries around the knee, or a large articular cartilage injury will cause us to recommend surgery sooner.Also, if we feel that an ACL Repair may be possible, we will likely move forward with surgery a little sooner as well.

This is why it is critical for patients to seek immediate care after major knee injuries, so all treatment options can be considered and the ideal timing for treatment can be planned.

If your range of motion is limited, we will give you stretching and gentle strengthening exercises to do before surgery.

Frequent icing will help decrease pain and swelling, as will anti-inflammatory medications like Advil, Motrin, ibuprofen, Aleve, or Naprosyn. Stop taking all anti-inflammatory medications 5-7 days prior to surgery to minimize bleeding during and after the procedure.

Surgery

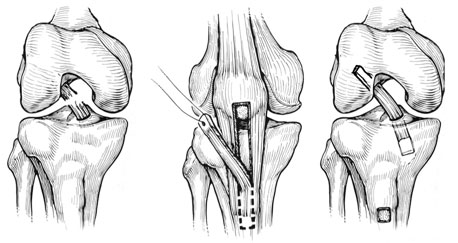

At Mammoth Hospital, ACL surgery is done with an arthroscope (a camera used to look into the joint) and three or four small incisions around the knee to look and work inside. Depending on which type of surgery is done, there may also be one or two slightly longer incisions on the front of the knee to harvest graft tissue.

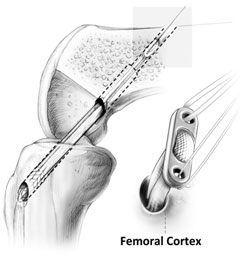

In reconstruction surgery, tunnels are drilled into tibia and femur and the graft is secured into the sockets. There will be some type of fixation (usually a tiny plate/button or screw) that keeps your graft secure in the tunnels while the graft heals to the bones.

In ACL repair surgery, suture anchors are used to dock the native ACL ligament back to the femur (after preparing the bone adequately to stimulate healing). While you are asleep, we will examine the other ligaments around the knee, look at your meniscus and articular cartilage, and treat any associated injuries.

Graft Choice

As mentioned above, there are different graft options available for ACL reconstruction. There are pros and cons to each; which type we recommend will depend on your age, activity level, and associated injuries. There are many choices and there is no right or best graft for everyone. Graft choice should be the result of an informed discussion between you and your surgeon.

Autografts are tissues from your own body. General advantages of autografts over allografts are:

- Faster incorporation/healing time (although the overall rehab time is similar compared to allograft)

- Less expensive

- For patients younger than ~25 years of age, recent research has suggested a 3.5-fold lower risk of revision surgery because of graft rerupture (15% risk with allograft, 4% with autograft: MOON Trial, Sports Health 2011)

- No risk of disease transmission, like HIV or Hep C (although this is mostly theoretical—the risk of disease transmission from a cadaver graft is extremely low, less than 1 in 1 million according to the CDC)

Autografts:

There are three main autograft options:

-

Quadriceps tendon:

The quadriceps tendon straightens the knee, but it is located above the

patella (kneecap) and may therefore be less likely to cause pain in the

front of the knee and difficulty kneeling than other grafts. While this

graft can be harvested with a bone block, new technology has allowed

for us to harvest this tendon without a bone block through a minimally

invasive incision approximately one inch long. Quadriceps grafts have

been proven to be at least as strong as BTB grafts and almost twice the

volume. Quadriceps grafts are always of adequate size and never require

additional allograft tissue, and thus share many advantages of both of

the other autograft types. Microscopic studies of the quadriceps tendon

have shown that its features are more like the normal ACL than other

graft choices.

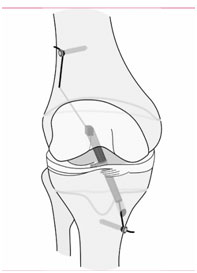

Quadriceps grafts are less commonly used nationally than the other two types of autografts. Part of this is because the length of the tendon demands that the all-soft tissue quadriceps grafts be implanted using an “All-inside technique”. Since this is a relatively new, but clinically proven, technique, many surgeons are not as familiar or comfortable utilizing it.

Dr. Crall and Dr. Gilmer developed and described a technique for securing the quadriceps tendon graft that facilitates all-inside implantation.Furthermore, at MOI we have tracked patient outcomes using our SOS (Surgical Outcomes System) registry and have compared our results for quadriceps autograft to other graft choices and found benefits over the other techniques.

Even considering all of this, it’s important to discuss graft choice as part of the preoperative planning process as many factors can ultimately affect the graft choice decision.

- Patellar tendon grafts use the middle 1/3 of the patellar tendon with bone pieces on each end— one from the patella and one from the tibia. The bone ends are typically fixed in the tunnels with large screws, ultimately with bone to bone healing, which is strong and reliable. Patellar tendon grafts are often used for young active individuals (16-23 years old) that play sports like football, soccer, and lacrosse. The downside to using this graft is that it can be more painful right after surgery than other graft choices. There is also an increased risk of having pain or cartilage wear behind the kneecap, which can last well after rehab is complete. It is estimated that 20% of patients experience this, although it has lessened with newer rehabilitation techniques. In addition, the rehabilitation with a patellar tendon graft is more intense and takes more effort than for other graft types. This graft has had extensive use in the athletic community over the past thirty years.

- Hamstring grafts use two of the five hamstring tendons from the inside of the knee. These two tendons are sewn together to create a “quadrupled” graft. This graft can be fixed to the bone tunnels with a variety of methods. Advantages include less pain in the front of the knee compared to patellar tendon graft. There is little noticeable loss in knee flexion (hamstring) strength. The downside to using the hamstring tendon graft is that it can cause some widening of the bone tunnels over time (the significance of this is unknown), and in some patients the harvest site continues to cause a cramping type of pain after rehab is complete. There has also been some recent concern over the smaller diameter of this graft and resulting higher rerupture rates in certain patients.

Allograft:

Allograft is donated (cadaver) tissues. There are a few different kinds that are used routinely:peroneus longus, patellar tendon, and Achilles tendon are common choices. The strength of these is very similar to the native ACL. The fixation methods vary depending on the type of tendon used, but in general all seem to work well.

Allograft is an attractive option because we do not remove anything else from your knee. Because of this, the early post-operative period is less painful, and patients tend to be on their feet more quickly. In addition, allograft is often the best or only option for individuals who requiremulti-ligament knee surgery or revision surgery.

As soon as the allograft tissue is placed into the knee, it begins a rebuilding and remodeling process similar to the other graft types. The collagen in the allograft acts as a scaffold for your cells so that over time, the allograft tissue becomes part of you. Thus, the healing and remodeling process takes a bit longer with an allograft, even though you feel better more quickly. This means that we slow down your rehabilitation to protect the graft while it heals. This also generally means a longer time before returning to sports (ask your surgeon).

The downside of using allograft tissue is that it is not from your own body. As a result, there is a small risk of viral and bacterial disease transmission. The risk of contracting HIV or hepatitis from a graft is estimated to range from 1 in 600,000 to 1 in 1.6 million. Current allograft screening and preparation techniques are very rigorous. As such, in the last five years, the risk of bacterial and/or viral transmission has largely become a theoretical risk. The biggest risk of allografts is a higher failure rate (rerupture rate) compared to autografts in younger patients (roughly 25 years old and under—see above).

The key to selecting the best graft for you is to have an informed discussion with your surgeon. Most importantly, the graft you select should be one you are comfortable having in your knee, and one your surgeon is comfortable putting in.

Postoperative Timeline

Your rehabilitation and return to activity depend on a number of factors including graft type, associated injuries and their treatments, and your surgeon’s preferences. This is only a rough guideline of what to expect, and you should discuss the specifics of returning to activity with your surgeon.

- Crutches for 1-3 weeks post operatively. These are stopped when your quadriceps muscle starts working again.

- Physical therapy 2-3 times per week, with an additional home exercise program.

- Your surgeon may want you to use a brace to protect the knee after surgery. He or she may also recommend a functional brace for sports and activities for a year or more after surgery.

- Return to team sports (assuming appropriate progression with therapy) at 6-12 months, depending on the graft type and sport.

-

When you return to work depends on your job:

- School, sedentary or desk work— 1-2 weeks

- Light duty (more walking or standing) — 3-6 weeks

- Heavy labor— 3-6 months

Risks

This surgery is complex and there are some specific complications that can occur:

- Post-operative fluid in the knee (can require drainage in the office)

- Continued pain and stiffness due to scarring in the knee or around the graft, occasionally requiring surgery to restore motion

- Need for re-operation to address a new meniscal tear or scarring

- Re-tear or progressive loosening of the graft

- New meniscus tear or articular cartilage injury

- Development or progression of knee arthritis

A more general complication of surgery can also occur and would include:

-

Deep venous thrombosis (aka “blood clot” or DVT)

- If you have a history of clots, make sure to tell your surgeon—blood thinners may be used in this subset of patients to prevent clots after surgery

- Infection (all patients receive antibiotics at the time of surgery to decrease this risk)

- Nerve injury (associated with numbness, weakness, or paralysis)

- Vascular injury or compartment syndrome

- Complications associated with the anesthesia