Cody McGrale, MS-2, Brian Gilmer, MD

Anatomy

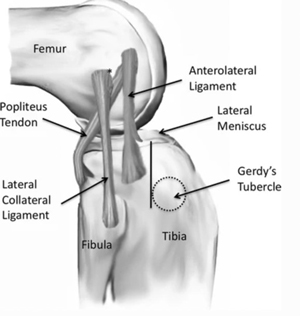

The anterolateral ligament (ALL) takes an oblique and anteroinferior course in the knee originating from the lateral distal femur and inserting onto the proximal anterolateral tibia.1 There is variance between studies of the exact ALL origin with some studies reporting the origin to be just anterior to the LCL2, but others report its origin to be posterior and proximal to the LCL.1 The insertion is believe by most studies to be on the proximal tibia in between the head of fibula and Gerdy tubercle, but some variance has been noted including inserting on the lateral meniscus.1,6

Biomechanics

The ALL is thought to be an important secondary stabilizing ligament for internal tibial rotation control during pivot shift and with increasing knee flexion (angles>35°) to provide rotational stability to the knee.3,4 When the knee is flexed greater than 35°, the contribution of the ALL to internal rotational control was shown to exceed the ACL, so injury to the ALL can result in knee instability at high angles of knee flexion.5 The ALL is commonly simultaneously torn with the ACL, and many studies suggest that reconstructing the ALL during ACL reconstruction improves rotational knee stability more than ACL reconstruction alone.1

Indications

ALL reconstruction is indicated in patients <30 with:

- ACL revision surgery9

- High-grade pivot shift test9

- Chronic ACL tears (12 months)9

- Segond fracture9

- Lateral femoral notch sign on imaging9

- Participation in pivoting sport/high demand athlete9

- Anterior tibial translation difference >7mm 4

- Continued clinically significant instability after ACL reconstruction7

Causes

ALL tears are caused by similar actions as ACL tears such as:

- Changing direction quickly8

- Stopping suddenly8

- Receiving direct impact to the knee8

- Landing awkwardly after jumping8

- Pivoting with your foot firmly planted4

- Pivoting sports4

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is typically made based on a constellation of items. A diligent surgeon will have a high suspicion for injury based upon the mechanism, meaning how the injury happened. The hallmark of a significant ALL injury is a high grade pivot shift. This is the specific three part motion of a twisting knee motion generally reproduced by the surgeon’s hands by 1) loading the leg axillay 2) placing a internal rotation force on the ankle (twisting the ankle inward) and 3) slowly flexing the knee. In general, a knee with an intact ACL will have little to no motion with this maneuver (grade 0 or sometimes called a pivot glide). With more involvement of the anterolateral capsular injury incombination with an ACL tear, the knee will clearly shift- this happens because of the reciprocal action of the IT band. In extension the knee can be subluxed forward on the lateral side by the examiner’s hand, as the knee flexes, the IT band moves from being an extender to a flexor and it will pull the knee backwards as higher flexion occurs. This reduces the subluxation created by the examiner and creates the characteristic shift that is perceived (grade 2) or some cases you can even see it happen (grade 3). Grade 2 and 3 injuries become more concerning to the surgeon who may feel that additional support of the anterolateral ligament complex is required based on the factors listed above in the indications section.

Ultrasonography, and MRI can be helpful but are often not definitive even in the case of a skilled examiner, especially if some time has elapsed since the knee injury. Thus, the pivot shift test is most commonly used to diagnose an ALL injury, and it takes some time for even a skilled examiner to get the hang of this maneuver.4,7 this is one reason why it is important to have an experienced knee surgeon who is specifically looking for ALL injury. MRI is used to confirm the diagnosis but is typically not commented on in an MRI report unless it is very obvious.

It is worth noting that a Segond sign is seen on radiographs even better than on MRI and this is just one of many reasons why it is important to have both x-rays and an MRI to fully evaluate a knee ligament injury. With the Segond sign, a small fleck of bone is thought to avulse (pull off) from the tibia bone. Since this is the most obvious sign of ALL injury it is often treated with a repair (using your own tissue) or reconstruction (using a graft to make a new ligament to reinforce the anterolateral knee. This band of tissue prevents the anterior (forward) subluxation of the lateral side of the knee thus preventing the pivot shift.

Figure 2 – Segond Fracture

Figure 2 – Segond Fracture

Procedure

ALL Reconstruction

ALL reconstruction is usually performed at the same time as the ACL reconstruction. The surgeon will create the ALL tibial tunnel and mark the position for entry for outside-in drilling of the femoral tunnel. Using either a semitendinosus, gracilis, or quadricep, the combined ACL and ALL graft will be prepared. The femoral tunnel will then be drilled at the anatomical location of the ALL. A suture passing technique will be used to pass the graft through the tibial tunnel and through the femoral tunnel ensuring proper tension is created. The ALL graft is then shuttled from the femoral tunnel to the tibial tunnel and back on itself (see below).9

Modified Lemaire Lateral Extraarticular Tenodesis

There are many variations on this technique and the most common is the modified Lemaire Lateral Extraarticular Tenodesis or LET. This technique uses the patient’s own iliotibial band (just a part of it) as the graft. This portion about 7cm long and 10mm wide is tubularized (made round with use of sutures) and then secured in the appropriate position, generally posterior and proximal to the lateral epicondyle, generally below the LCL though in some cases it is placed over the LCL by some surgeons. This has the advantage of using the patients own tissue, and avoids the need for another tunnel because the IT band attaches to Gerdy’s tubercle very close to the attachments of the anterolateral ligament complex.

Post-Operative Rehabilitation

After surgery, patients are placed in a locking hinge brace limiting joint range of motion to <50° of flexion for the first 2 weeks with only partial weightbearing. The brace will be changed to allow up to 90° of knee flexion with full weightbearing with crutches for the next 4 weeks.10,11 An ACL brace is recommended for weeks 6-12 weeks after surgery and sometimes longer.10 Full return to sports activities is typically recommended after 8-9 months post-operatively.9

Since ALL injuries rarely happen without ACL injury (some say that this is not possible at all without an ACL injury) the rehab is largely determined by the other procedures which are performed. This is why it is important to have a skilled physical therapist to assist with following the correct protocol.

Risks and Complications

The risks and complications of the ALL are the same as ACL reconstructions and other orthopaedic surgeries.

These possible risks and complications include:

- Re-tear

- Infection

- Post-op knee pain

- Limited range of motion

- Meniscus injury

There is also some concern about the concept of lateral overconstraint or making the knee too tight. This is a topic of much discussion among knee surgeons but the most important message is that ALL surgery should be considered against the other risk factors and the unique injury and not just performed reflexively in all cases. A thoughtful surgeon will have a clear rationale for why and when they perform additional ALL surgery during ACL surgery.

References

- Patel, Ronak M, and Robert H Brophy. “Anterolateral Ligament of the Knee: Anatomy, Function, Imaging, and Treatment.”The American journal of sports medicine 46,1 (2018): 217-223. doi:10.1177/0363546517695802

- Claes, Steven et al. “Anatomy of the anterolateral ligament of the knee.”Journal of anatomy 223,4 (2013): 321-8. doi:10.1111/joa.12087

- Cianca, John et al. “Musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging of the recently described anterolateral ligament of the knee.”American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation 93,2 (2014): 186. doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000000070

- Sonnery-Cottet, Bertrand et al. “Anterolateral Ligament of the Knee: Diagnosis, Indications, Technique, Outcomes.”Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association 35,2 (2019): 302-303. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2018.08.019

- Parsons, Erin M et al. “The biomechanical function of the anterolateral ligament of the knee.”The American journal of sports medicine 43,3 (2015): 669-74. doi:10.1177/0363546514562751

- Vincent, Jean-Philippe et al. “The anterolateral ligament of the human knee: an anatomic and histologic study.”Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA 20,1 (2012): 147-52. doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1580-3

- Chahla, Jorge et al. “Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction Technique: An Anatomic-Based Approach.”Arthroscopy techniques 5,3 e453-7. 9 May. 2016, doi:10.1016/j.eats.2016.01.032

- Shekari, Iraj et al. “Predictive Factors Associated with Anterolateral Ligament Injury in the Patients with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear.”Indian journal of orthopaedics 54,5 655-664. 1 Jun. 2020, doi:10.1007/s43465-020-00159-7

- Saithna, Adnan et al. “Combined ACL and Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction.”JBJS essential surgical techniques 8,1 e2. 10 Jan. 2018, doi:10.2106/JBJS.ST.17.00045

- Murray, Martha M et al. “Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair: Two-Year Results of a First-in-Human Study.”Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 7,3 2325967118824356. 22 Mar. 2019, doi:10.1177/2325967118824356

- Murray, Martha M et al. “The Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair (BEAR) Procedure: An Early Feasibility Cohort Study.”Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 4,11 2325967116672176. 21 Nov. 2016, doi:10.1177/2325967116672176

Dr. Gilmer’s Take:

This is an important concept in knee surgery right now (2023). An article in the New York Times created quite a stir when it highlighted the discovery of a “new” knee ligament. www.archive.nytimes.com/well.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/13/a-surprising-discovery-a-new-knee-ligament

In reality, surgeons have known about the anterolateral ligaments for a long time and many older procedures performed for ACL surgery addressed this. One procedure, the modified McIntosh (no relation to the computer) which is still common in pediatric ACL surgery where the surgeons must avoid damaging the growth plate, uses a strip of IT band and wraps it around the back of the knee effectively recreating both the ACL and the ALL. Calling the ALL a ligament may be misleading as it really more like a thickened part of the knee capsule or joint lining. In real experience, after dissecting several cadaver knees, some surgeons can always find the ALL, others only sometimes, and some deny being able to reliably isolate it all. If that is not enough, there is even more disagreement over where this ligament attaches on the femur and tibia bones. Perhaps the more important item is the concept of the ALL, namely that there is tissue on the front and outside part of the knee that prevents abnormal rotation.

Nonethelesss, there is definitely renewed interest in ALL surgery after the STABILITY trial-- (Getgood AM, Bryant DM, Litchfield R, Heard M, McCormack RG, Rezansoff A, Peterson D, Bardana D, MacDonald PB, Verdonk PC, Spalding T. Lateral extra-articular tenodesis reduces failure of hamstring tendon autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: 2-year outcomes from the STABILITY study randomized clinical trial. The American journal of sports medicine. 2020 Feb;48(2):285-97.) taught us that we could reduce the risk of re-rupture after ACL injury by adding the LET procedure. There is a lot in this well done trial, but a commonly quoted portion is that the graft rupture rate (the new ACL graft ripping apart like the native ACL) went from 11% in those having reconstruction alone to 4% in the ACL+LET group. In the world of knee surgery this is a pretty large reduction of risk.

The question remains for some, what is the downside? Some biomechanical studies show that the LET makes the knee too tight and that this may aggravate cartilage wear over time. Having too much motion also has negative effects so careful judgement is required to consider who needs LET or ALL reconstruction with their ACL surgery.

In my practice, I routinely will perform ALL surgery for the following reasons:

Revision ACL (a previous ACL graft tore)- If the patient tore the first graft, it is worth doing all we can to reduce this risk of recurrence another time

High Risk Athlete- this is generally younger patients who do cutting and pivoting and some examples are skiing, soccer, football, rugby, and jiu jitsu among others.

Segond Fracture- That pulling the ligament off the bone, I will often perform a repair of this, though it can be difficult to find this small fragment and in some cases an LET is better

High Grade Pivot Shift- These knees really want to twist too much and this will exert forces on the ACL graft that would benefit from additional stabilization

Chronic- If the ACL has been torn for more than 1 year the knee has become accustomed to too much motion and additional stability can help. We know that chronic ACL treatment is not quite as good as having it done earlier on, for a variety of reasons outside our scope here.

I prefer the LET technique, and my article with Dr. Chris Wahl of Seattle which is being released later this year in the Arthroscopy journal shows how this is done. I like the LET technique because it is a bit less invasive for the patient and works very well. This technique uses only suture which is nice because the ALL attachment is very close to the tunnel used for the ACL and these can intersect with other techniques despite a surgeon’s best efforts.

If you have more questions about LET and how the ALL applies to your knee or injury please feel free to reach out on the Contact Us page.

Brian Gilmer

Biography: Cody McGrale is currently a second-year medical student at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.