Zoe Anderson MS2, Brian Gilmer, MD

Introduction

Matrix-Induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI) is a 2-stage surgical intervention that may be indicated in the treatment of symptomatic, full-thickness chondral lesions located in the knee.1 Case series suggest that MACI can successfully treat symptomatic isolated cartilage defects, improving pain and function.3

If this sounds a little jargony, it is. The idea is that in some cases where there is just one area of cartilage damage in a knee without full blown arthritis, we can perform an arthroscopic surgery (just a couple small poke holes using a small camera) and measure the missing cartilage area, then take a small sample of your own cartilage, send it to a lab where the cells are multiplied and then placed on a membrane or matrix. These cells can then be sent back to the surgeon and implanted into the defect.

A helpful analogy would be like filling a pothole in the road if the cartilage was the road surface and the missing cartilage area was the pothole. The MACI graft is for areas where only cartilage and not bone are involved.

Indications

MACI is indicated in: symptomatic, full-thickness osteochondral lesions >2 cm2; bone deficiency with cavitary defect measuring >8 mm in depth; femoral condyle, trochlea, patella, or tibial lesions resulting from osteochondritis dissecans, osteonecrosis, post-traumatic osteochondral defects, or localized osteoarthritis; young, high-demand patients who are not a candidate for arthroplasty; BMI <35.1

MACI is contraindicated in: instances of advanced degenerative changes affecting multiple compartments of the knee; uncorrected lower extremity malalignment; uncorrected ligamentous instability; meniscal insufficiency; inflammatory arthritis.1

This is a complicated way of saying that not everyone is a good candidate for MACI. If you are going to have two surgeries to solve a problem, you really want it to work. A thoughtful surgeon will recognize who is a candidate for a MACI procedure and take many things into account such as the patient’s weight, activities, the type of the injury, its size, how deep it is, and what the condition of the rest of the knee is.

Causes

Full-thickness chondral lesions located in the knee can be caused by:

- Acute trauma2

- Repetitive trauma2

- Abnormal joint loading3

- Osteochondritis dissecans3

The aforementioned, among other causes, can cause full-thickness chondral lesions. Full-thickness defects do not spontaneously heal, and instead have a limited ability to heal.2 Chondral lesions have limited healing ability due to due to their avascular character, as well as the declining function of the damaged chondrocytes.

This means that cartilage cells are like brain cells, they do not divide and heal themselves like your skin or muscle cells can. So while a cut on your arm will heal very reliably, the cartilage cells tend to die and flake off. This leaves an area of exposed bone. Normally cartilage sliding across cartilage when a person moves is as smooth as ice on ice. But bone is like ice on sandpaper. This roughness can cause pain and swelling and limit activity.

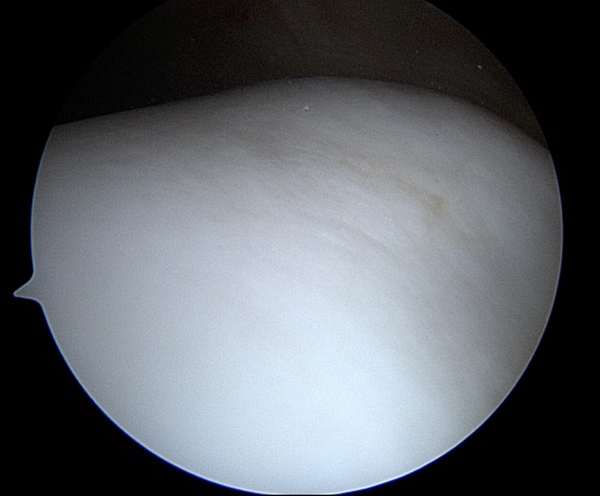

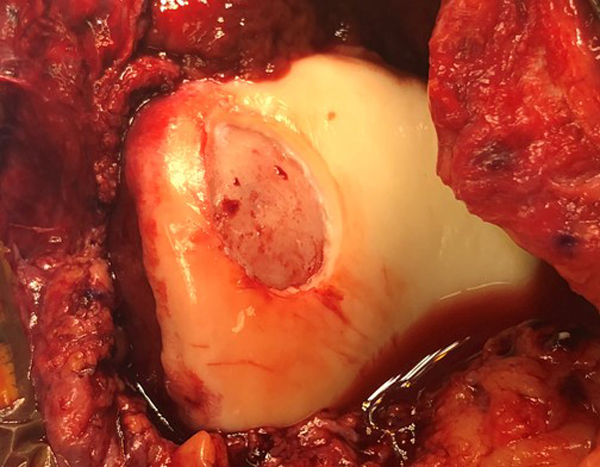

Figure 1

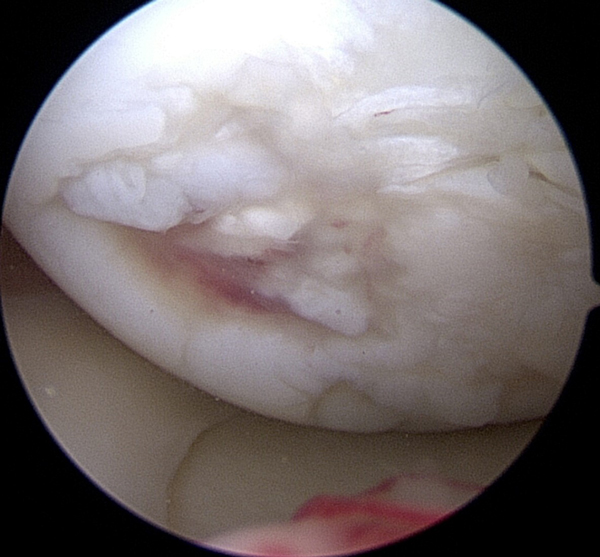

Figure 1

This is a picture of normal cartilage taken with an arthroscopic camera, it looks perfectly smooth and white. The camera is the size of a pencil and takes pictures that are magnified. This is the groove under the knee cap (trochlea) of a young healthy athlete who was having surgery for other reasons.

This is an arthroscopic picture of a high grade cartilage injury. The surface is not smooth, remember the pothole analogy. The red area is exposed bone. It is not hard to imagine how this would not be as smooth when rubbing on the normal white cartilage below it. This picture is taken on the inside part of the femur bone (the condyle) and this patient later had a cartilage repair procedure. It is important to note that in this picture the area around the full thickness cartilage defect is not healthy either and this is one reason why MRI images tend to underestimate how big the area of cartilage damage is.

Diagnosis

A surgeon or orthopedic specialist can diagnose cartilage injuries based on medical history, physical exam, and imaging such as radiography and MRI.

Typically, this means listening to the patient, examining the knee, then getting x-rays, mostly to check for arthritis and other problems in the knee. Cartilage does not show up on x-rays and so it most typically appears normal even with a pretty large defect. This is like the pothole not showing up when you are just looking at the whole road.

An MRI is a 3D picture of the knee taken with powerful magnets that allow us to map where the water is in the knee. An MRI typically will show a cartilage defect but tends to underestimate the size.

With MACI procedures, the thoughtful surgeon may also order alignment xrays to make sure there is not too much pressure or another reason for the cartilage damage to have occurred. This may not be a reason not to do the MACI procedure, but it may mean that other procedures are needed at the same time to get the best result, like an osteotomy. In some cases, ligament or meniscus surgery is required at the same time as well.

All of this is part of making sure a patient is a good candidate for MACI.

Procedure

MACI consists of two separate surgical procedures. The first procedure consists of arthroscopy to assess the degree of the lesion. This first procedure also includes the harvest of patient chondrocyte.

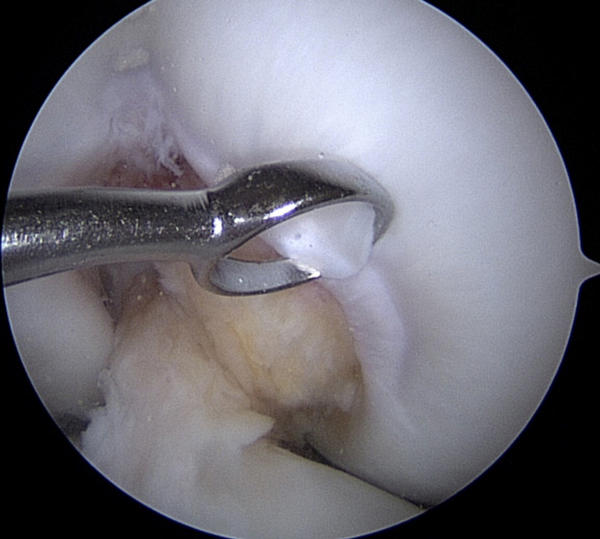

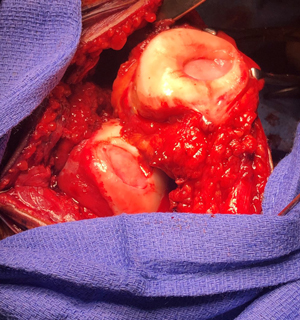

Figure 2

Figure 2

This shows a small curette (it’s like a tiny ice cream scoop) taking a sample of healthy cartilage from a part of the knee where there is no weight bearing. This is usually from the notch area by the ACL and PCL (the cruciate ligaments in the middle of the knee). Remember the arthroscopic camera takes very magnified images. This piece of cartilage is about the size of the head of a pin. Usually 3-4 samples are taken in the MACI procedure.

Once the chondrocyte is obtained, it can be sent to a laboratory to be cultured and expanded. Prior to the second procedure, which consists of chondrocyte implantation into the patient, the expanded chondrocyte cultures are seeded onto a scaffold, or membrane, which your surgeon will implant into the damaged area.3 The purpose of the second procedure is to implant the chondrocyte scaffold into the patient. It can be performed via either an arthroscopic or open approach, determined by the size and location of the chondral lesion.3 The implant is perfectly matched to the defect and is set with a minimal amount of fibrin glue.3

In reality, this almost always requires an open incision in the knee, sometimes with the assistance of the camera.

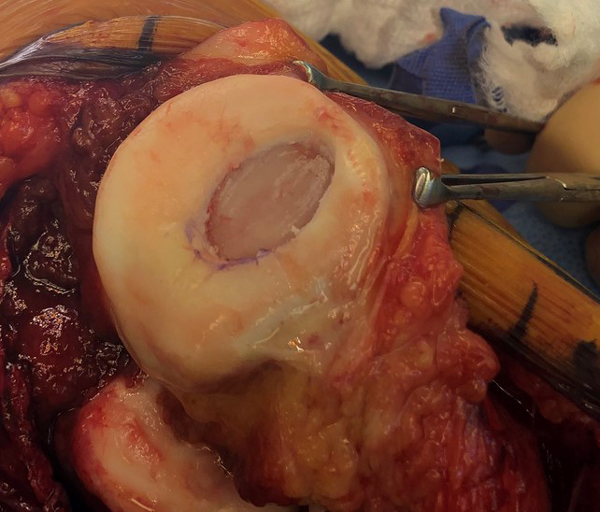

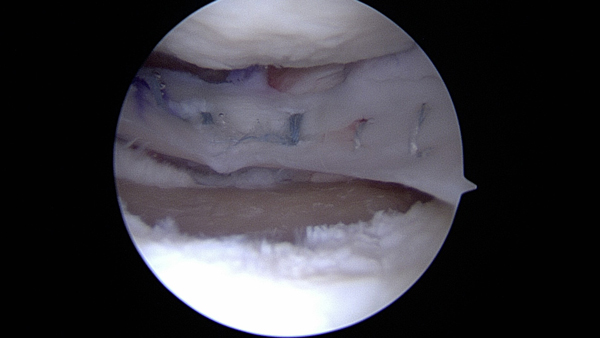

Figure 3

Figure 3

In the top image the knee cap has been flipped open. There is an open incision on the knee which is why there is more blood in these pictures than the arthroscopic ones. The lesions have been removed and vertical edges created. These two lesions are ready to receive the MACI graft.

Figure 4

Figure 4

The MACI implant has the patient’s own cells on a thin flexible membrane. It is rather delicate, like a piece of wet toilet paper or paper towel. The membrane can be cut to fill the defect using some predesigned shapes, like cookie cutters.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Here two MACI implants have been placed one on the trochlea (groove for the knee cap) and one on the patella (knee cap – it’s been flipped over in this picture to get to it). They look like little ovals. They will be glued into place with an absorbable glue. These are actually the two defects from the patient above in Figure 3. The membrane has been cut to perfectly match the defects. After this the knee will be sewn back up in layers.

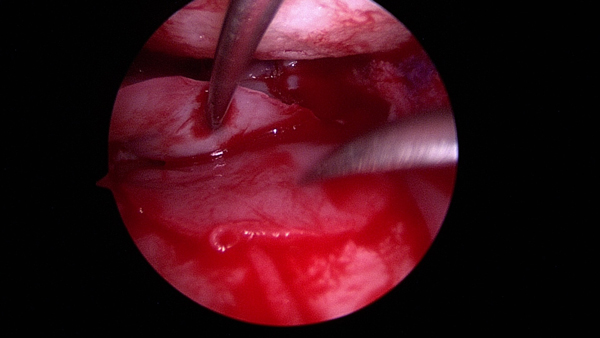

Figure 6

Figure 6

In the top picture a defect is present underneath a meniscal allograft on the lateral (outside) part of the knee. The yellow area is exposed bone. The white in front of it is normal cartilage. This location is very hard to reach so a small incision is made and the arthroscopic camera is used to assist. In the bottom picture the MACI graft has been placed with some small instruments and a needle is used to hold the meniscus graft out of the way temporarily. The MACI graft covers the yellow area of exposed bone. This is an example of an arthroscopic approach to MACI grafts.

Post-Operative Care

Post-operatively, there is a brief period of immobilization, during which continuous passive motion is advised.3 Usually it is advised to follow 8-12 weeks of limited weight bearing and progressive range of motion.3 Increasing activity level can follow this time period. Full return to sports activities is typically advised to wait 18 months post-op.3

These general recommendations are from the manufacturer and some variety occurs based on individual cases.

Risks and Complications

- It is unknown whether MACI is safe or effective in people under age 18 and over age 55.5 It is also unknown whether MACI is effective in locations other than the knee.5

- Should not be used in patients allergic to antibiotics such as gentamicin.5

- Should not be used in patients allergic to materials derived from cow, pig, or ox.5

- Should not be used in patients who have severe osteoarthritis of the knee, other severe inflammatory conditions, infections or inflammation in the bone joint and other surrounding tissue, or blood clotting conditions.5

- Should not be used in patients who have had knee surgery in the past 6 months, not including surgery for obtaining a cartilage biopsy or a surgical procedure to prepare your knee for a MACI implant.5

- Should not be used in patients who cannot follow a doctor-prescribed rehabilitation program post-operatively.5

As with any knee surgery, possible risks include knee stiffness, infection, blood clots, nerve and blood vessel damage, and ligament injuries.6 Common side effects of MACI include joint pain, tendonitis, back pain, joint swelling, and joint effusion.5

Dr. Gilmer’s Take-

The idea of MACI is very compelling for a variety of reasons. Patients get to treat their injury with their own cells and overall the procedure has minimal detrimental effects to the rest of the knee – what we call donor site morbidity.

The downsides are that the patient cannot have had a prior surgery like a microfracture, and that the procedure requires two surgeries 6 weeks a part and a pretty long recovery. It is not intended to treat lesions where the bone is involved.

In my practice, I typically use MACI surgery for the patellofemoral joint (the knee cap and groove under the knee cap) and less commonly for the tibia bone. On the femoral condyles, I tend to prefer an OATS procedure, or an OCA if the lesion is large. You can read about those procedures elsewhere in the EncycloKNEEdia.

Anecdotally, I have had the best results in younger patients and it is not successful for all patients and can require revision to OATS or OCA. So it should be pursued very thoughtfully and with a patient who is dedicated to the rehab protocol. The MACI website has a great host of additional information and is a good resource for patients interested in this procedure.

https://www.maci.com/patients/about-maci/

Brian Gilmer, MD February 2023

References

- Jones, K. J., & Cash, B. M. (2019). Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation with autologous bone grafting for osteochondral lesions of the femoral trochlea. Arthroscopy techniques, 8(3), e259-e266.

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2012, September 5). Orthopedic surgery. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved December 28, 2022, from www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/orthopedic-surgery/news/advances-in-articular-cartilage-defect-management/mac-20430210

- Jacobi, M., Villa, V., Magnussen, R. A., & Neyret, P. (2011). MACI-a new era?. Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology, 3(1), 1-7.

- Penttilä, P., Liukkonen, J., Joukainen, A., Virén, T., Jurvelin, J. S., Töyräs, J., & Kröger, H. (2015). Diagnosis of knee osteochondral lesions with ultrasound imaging. Arthroscopy Techniques, 4(5), e429-e433.

- Introducing MACI knee cartilage repair. MACI. (n.d.). Retrieved December 28, 2022, from www.maci.com/patients/about-maci/

- (n.d.). Total knee replacement (TKR). Total Knee Replacement Mammoth Lakes, CA. Knee Osteoarthritis CA. Retrieved December 28, 2022, from www.mammothortho.com/total-knee-replacement-mammoth-orthopedic-institute.html

Biography: Zoe Anderson is currently a second-year medical student at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.