Cody McGrale MS2, Brian Gilmer, MD

After an ACL tear, the primary objective of treatment is to reestablish knee stability as well as the native biomechanics and anatomic properties of the ACL.1 In general, ACL tears are treated with reconstruction, which means creating a new ACL with a graft.

This is in important distinction to ACL repair.

One might logically ask, why would you NOT just repair the ACL instead of replacing it. The story goes back at least 40 years. At that time MRI was not commonplace and it was not clear what was occurring in these knee injuries due to lack of imaging. Remember, in an ACL tear, the x-ray is typically normal.

At the time, most knee injuries were treated in a cast, and the patient was allowed to get very stiff and then slowly regain their motion with time in the hopes that this would restore stability. With time and increased understanding some surgeons began to open the knee or use arthroscopy, a very new technique at the time, to look inside the joint. They found that the anterior cruciate ligament was ruptured. Then attempts were made at repair. This was generally done by opening the knee and then sewing the ligament back to the wall of the femur. The problem was that this had very mixed results. About 50% of these repairs did not work. So other solutions were sought and eventually the modern ACL reconstruction was developed. This procedure is more reliable and has a roughly 85-90% success rate. Thus, ACL repair was largely abandoned.

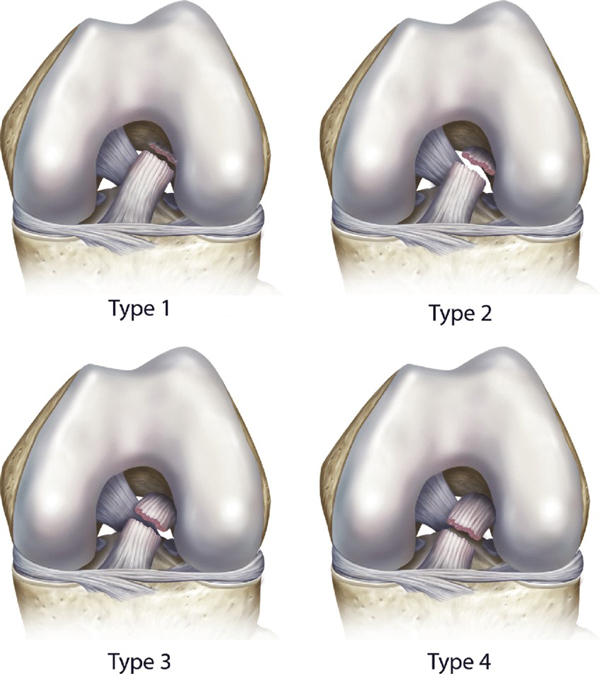

More recently, primary ACL repair surgery has regained favor for certain tear patterns most notably type 1 proximal avulsion tears with excellent tissue quality of the remnant ligament.1,2

What has changed is that we are now able to look more closely at the ACL, how it tore, where it tore, and realized 1)the limitations of the modern ACL reconstruction (they are not all perfect), and 2) that 50% of those prior repairs did work. The thinking has been that if we could better understand who those 50% are, we could perform repair in at least some patients, saving them the added morbidity and longer recovery of a graft.

Modern primary ACL repair involves reattaching the ACL back to its anatomical attachment site on the femur without the need to harvest an autograft from the patient which is needed in ACL reconstruction, and this eliminates any harvesting-related morbidity and complications.3 Primary ACL repair has also been reported to have fewer post-op infections, smoother rehab, and easier return to daily life activities and sprots.3,4 Studies have shown primary ACL repair to be most effective in proximal tears with less positive results in more distal tears.5

Indications

In general, primary ACL Repair is indicated in a proximal type I or II complete ACL rupture confirmed by MRI in skeletally mature patients 14 years or older.3,5 We like the tear to be relatively recent as well and the ACL stump remnant must have excellent tissue quality.1,2

Primary ACL repair is relatively contraindicated (that means not recommended) in type III and IV ACL tear, poor remnant tissue quality, and re-tear of previously repaired ACL.3

Causes

Complete ACL tears can be caused by:

- Changing direction quickly6

- Stopping suddenly6

- Receiving direct impact to the knee6

- Pivoting with your foot firmly planted6

- Landing awkwardly after jumping6

Diagnosis

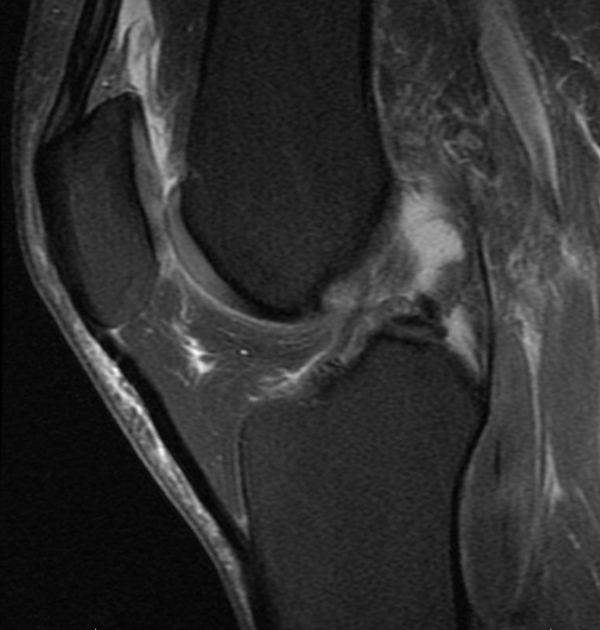

ACL injury is not always as obvious as you would think. And there is definitely a spectrum of tears from partial tears and strains, to tears of only one bundle (the normal ACL has two bundles which twist around each other). A thoughtful surgeon will make recommendations based on a careful history and physical exam along with an MRI. The Lachman test, anterior drawer test and pivot shift test are commonly used to diagnose an ACL injury.7 X-rays are needed to look for other issues in the knee such as cartilage wear or arthritis, and ultimately MRI is usually used to confirm a proximal tear that is a candidate for primary ACL repair. 5

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows a sagittal (View from the side) of an ACL tear that is a type 1. The ACL is the gray fibers between the larger darker grey femur and tibia. It does not look so bad, in fact the radiologist even indicated that it was normal.

But in the lower picture we see that the whole ACL has actually separated from the wall of the femur. In the picture, the white ligament in the middle should be attached to the vertical looking bone on the left of the screen. Instead it has scarred to the PCL ligament. This patient ultimately underwent an ACL repair to sew the ACL back to the femur bone.

This is an example of a type 2 tear. Again we see the black fibers of the ACL are mostly intact, but they are laying down. Normally they should be standing up like a sail or a tent. In the bottom image, we see that there is some ACL on the wall of the femur, the vertical looking bone on the right of the screen, but the big blobby looking thing in the middle left, the ACL, is not attached well and is loose. This patient also went on to undergo ACL repair.

Procedure

There are many ways to perform ACL repair. The following technique uses a small metal button and a nifty suture passing technique called a Fiber Ring repair. This is currently Dr. Gilmer’s favored technique in clinical practice though he has used suture anchor based repair in other cases with good success.

Technically speaking, an anteromedial portal, anterolateral portal, and central portal are created, and the ACL tear is visualized to confirm a type 1 or 2 tear with suitable tissue quality. A suture will be passed through the ACL remnant on the tibial side in a lasso-loop knot configuration. The sutures are then passed through the posterolateral and anteromedial bundles. A femoral tunnel is then made at the origin of the femoral stump without debriding the femoral stump. The ACL stitches are then passed through the femoral tunnel. The repair sutures are then pulled to tension by cycling the knee, and integrity of the ligament is confirmed at different degrees of knee flexion.3,8,9

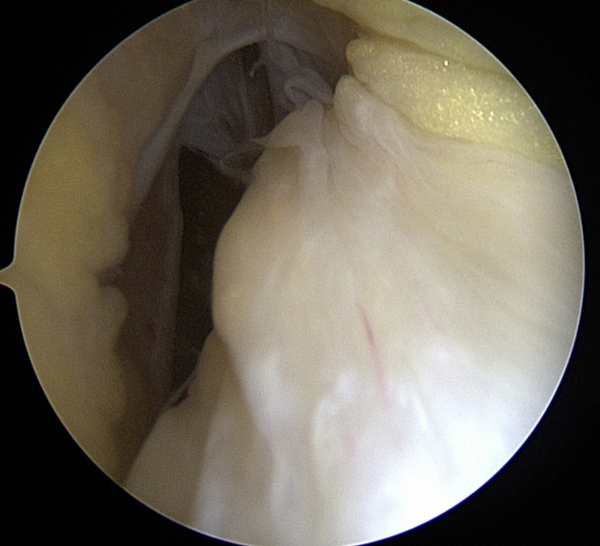

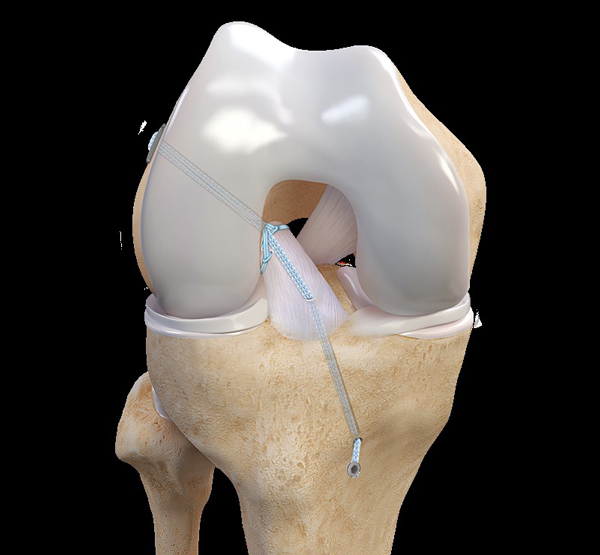

Figure 3

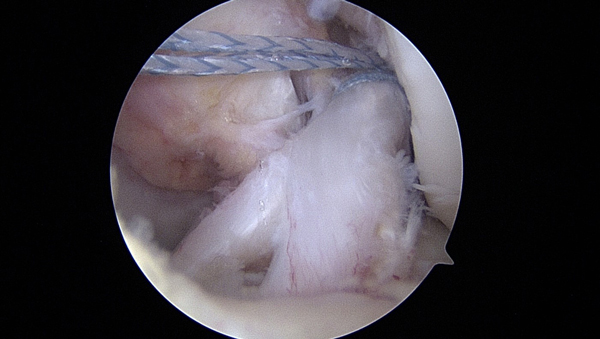

Figure 3

In the animation above, there are sutures placed in the ACL and a small metal button that rests outside the femur bone that allows these sutures to be cinched into place. An additional suture is placed to protect the repair, called an internal brace, which is then secured on the tibia bone.

The image below shows an arthroscopic image of the same thing. In this picture the internal brace suture has not yet been passed through the ACL and into the tibia bone.

A more detailed video of this technique is available here:

Post-Operative Rehabilitation

After surgery, patients are positioned in a hinge brace to limit joint range of motion with the goal of controlling swelling and regaining range of motion. Patients should expect to be in the brace for a few weeks, and then will start strengthening without the brace following the standard ACL rehab protocol.2,10 Full return to sports activities is typically recommended after 6-9 months post-operatively.11

Risks and Complications

The risks and complications of the primary ACL surgery are the same as ACL reconstructions and other orthopaedic surgeries.

These possible risks and complications include:

- Re-tear

- Infection

- Post-op knee pain

- Post-op knee effusion

- Limited range of motion

- Meniscus injury

- Development or progression of knee arthritis

- General surgery complications such as DVT, nerve injury, vascular injury, or anesthesia associated complications.

Dr. Gilmer’s Take

Only about 10% of ACL tears are type 1 tears that are considered best for ACL repair. In the future this number may expand. In general, I counsel patients that the risk of re-tear is higher than for reconstruction and that reconstruction is still the best option for most patients. That being said, patients with successful ACL repair often report that there knee feels more normal than a reconstructed knee, and the recovery is typically much easier in terms of pain and regaining motion and strength. Ultimately, like many things , this is a trade off. My job is to present patients with the best information and help them make an informed decision about their knee. Currently, we are writing a much larger review of this topic which will be published in a medical journal.

Brian Gilmer, MD - February 2023

References

- Taylor, Samuel A et al. “Primary Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament: A Systematic Review.”Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association 31,11 (2015): 2233-47. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2015.05.007

- DiFelice, Gregory S, and Jelle P van der List. “Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Primary Repair of Proximal Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears Are Maintained at Mid-term Follow-up.”Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association 34,4 (2018): 1085-1093. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2017.10.028

- Monaco, Edoardo et al. “Acute Primary Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament With Anterolateral Ligament Augmentation.”Arthroscopy techniques 10,6 e1633-e1639. 24 May. 2021, doi:10.1016/j.eats.2021.03.007

- van der List, Jelle P, and Gregory S DiFelice. “Range of motion and complications following primary repair versus reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament.”The Knee 24,4 (2017): 798-807. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2017.04.007

- van der List, Jelle P, and Gregory S DiFelice. “Role of tear location on outcomes of open primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament: A systematic review of historical studies.”The Knee 24,5 (2017): 898-908. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2017.05.009

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery. (2022 October). “Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries.” AAOS. Retrieved January 1, 2023, from www.orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/anterior-cruciate-ligament-acl-injuries/

- Spindler, Kurt P, and Rick W Wright. “Clinical practice. Anterior cruciate ligament tear.”The New England journal of medicine 359,20 (2008): 2135-42. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0804745

- Jonkergouw, Anne et al. “Arthroscopic primary repair of proximal anterior cruciate ligament tears: outcomes of the first 56 consecutive patients and the role of additional internal bracing.”Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA 27,1 (2019): 21-28. doi:10.1007/s00167-018-5338-z

- DiFelice, Gregory S et al. “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Preservation: Early Results of a Novel Arthroscopic Technique for Suture Anchor Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair.”Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association 31,11 (2015): 2162-71. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2015.08.010

- Wilk, Kevin E, and Christopher A Arrigo. “Rehabilitation Principles of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructed Knee: Twelve Steps for Successful Progression and Return to Play.”Clinics in sports medicine 36,1 (2017): 189-232. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2016.08.012

- Saithna, Adnan et al. “Combined ACL and Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction.”JBJS essential surgical techniques 8,1 e2. 10 Jan. 2018, doi:10.2106/JBJS.ST.17.00045

Biography: Cody McGrale is currently a second-year medical student at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.