Cody McGrale MS2, Brian Gilmer, MD

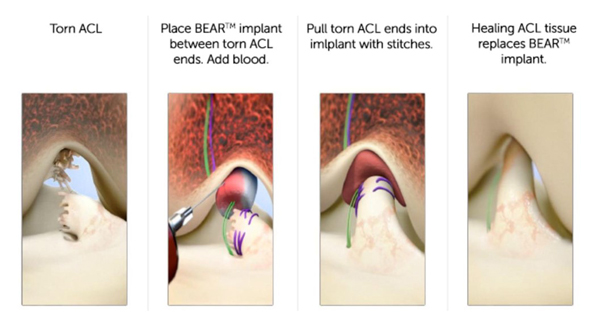

Bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair (BEAR®) is an alternative procedure for the conventional ACL reconstruction in which an extracellular scaffold (BEAR scaffold) is positioned between the two torn ends of the ACL to promote ligament healing without the need for allografts or autografts.1 Studies suggest that the BEAR® Implant was superior in conserving the physiological alignment and properties of the native ACL which can decrease tibiofemoral cartilage damage.2

Indications

The BEAR® Implant is indicated in a complete ACL rupture confirmed by MRI in skeletally mature patients 14 years or older. The ACL stump must be still fixed to the tibia in order to perform the repair.1 The BEAR® Implant must be used within 50 days of the initial tear.

Causes

Complete ACL tears can be caused by:

- Changing direction quickly3

- Stopping suddenly3

- Receiving direct impact to the knee3

- Pivoting with your foot firmly planted3

- Landing awkwardly after jumping3

ACL injuries are one of the most common orthopaedic surgeries performed worldwide because a torn ACL does not spontaneously heal without treatment.4,5

Diagnosis

Your medical provider will diagnosis your ACL injury based on a careful history and physical exam along with an MRI. The Lachman test and pivot shift test are commonly used to diagnose an ACL injury. MRI is the gold standard to confirm an ACL injury. 5

Figure 1 (Would like to include MRI of complete ACL Tear)

Figure 1 (Would like to include MRI of complete ACL Tear)

Procedure

The BEAR® Implant procedure only requires one surgical wound site, unlike ACL reconstruction surgery which requires two sites. The procedure starts with inserting sutures into the 2 ends of the torn ACL and placing a proteinaceous sponge scaffold (BEAR® Implant) between the two torn ends.2 Blood obtained from the patient is injected into the sponge which promotes ligament healing. The two ends of the torn ACL are pulled into the sponge. The body will replace the sponge to connect the two ends of the ACL over 8-12 weeks.2

Post-Operative Rehabilitation

After surgery, patients are placed in a locking hinge brace to limit joint range of motion to a max of 50° of flexion for the first 2 weeks and allowed only partial weightbearing. The next 4 weeks they were allow up to 90° of knee flexion and full weightbearing with crutches.1,6 An ACL brace is recommended for weeks 6-12 weeks after surgery.6 Full return to sports activities is typically recommended after 8-9 months post-operatively.8

Risks and Complications

The risks and complications of the BEAR® Implant surgery are the same as ACL reconstructions and other orthopaedic surgeries.

These possible risks and complications include:

- Re-tear

- Infection

- Post-op knee pain

- Limited range of motion

- Meniscus injury

Dr. Gilmer’s Take

I have written a separate section on this and that additional information can be obtained here as well as some information about my general approach to ACL injury and reconstruction.- www.briangilmermd.com/acl-reconstruction-knee-sports-medicine-specialist-reno-nv/

ACL injury is a huge topic. I could talk about it all day, but my feelings about the BEAR implant are published here again:

My opinion is that after reading the available medical literature and trialing carefully selected cases, I am excited about the potential that the BEAR implant may have for some patients.

I have conducted ACL repairs (sewing the patient’s own ligament back to the bone instead of replacing it) since 2015, but these have been in very selected cases. The reason is because the ACL has to tear in a very unique way for this to be successful. In studies dating back to the 1980s there was a high failure rate of ACL repair and that in part led to widespread adoption of reconstruction techniques. However, a smaller subset of these patients, skiers in particular had lower energy twisting injuries that tore the ligament from the bone but did not rip apart the fibers in doing so. Within that smaller population, again many of which were skiers, there were good long term results. This led me to look for these patients who might be good candidates for primary repair and with time we have been able to identify these better and classify patients better according to the pattern of the tear and the quality of the remaining ACL tissue. Unfortunately, only about 10% or less of patients had this type of tear off the femur bone, now commonly referred to as a Sherman type 1 or Sherman 1 bundle type 1 tear. These patients who have had successful ACL repair have generally had faster and less painful recoveries than those undergoing reconstruction. This intuitively makes sense since only a portion of the native ligament has to heal instead of the entire ligament having to be replaced with cells from the patient, a process called ligamentization, that occurs with grafts.

The attraction of the BEAR implant in my practice is that it could expand the number of candidates for ACL repair or preservation to include Sherman type 2 tears. These tears still have much of the tissue on the tibia stump, and often have good tissue quality, but would not quite reach the wall of the femurif they were simply repaired with suture. Type 2 proximal tears are defined as tears within 75% - 90% of the way between the tibia to the femur. The BEAR implant may be able to bridge these small gaps in the tendon and allow the patients healing cells to reach the wall of the femur. In my practice, the BEAR implant is always added in conjunction with a primary repair of the native ligament. Currently, the standard practice is to perform reconstruction of type 2 tears.

It’s possible that the BEAR implant may eventually have the proven data to support its use in even type 3 or 4 tears – those where there is less stump remaining, and generally tissue quality is poor. At this time, I recommend reconstruction for these types of tears as the safest and most reliable option but will continue to follow the literature on this evolving technology as we look for its place among the options that we can offer patients with these injuries.

Brian Gilmer - February 2023

References

- Murray, Martha M et al. “Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair: Two-Year Results of a First-in-Human Study.”Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 7,3 2325967118824356. 22 Mar. 2019, doi:10.1177/2325967118824356

- Rodoni, Bridger M & Eyrich, Nicholas W. “The Bridge-Enhanced ACL Repair: A Review.” Michigan journal of medicine. 4,1. May 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/mjm.13761231.0004.114

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery. (2022 October). “Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries.” AAOS. Retrieved January 1, 2023, from https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/anterior-cruciate-ligament-acl-injuries/

- Mall, Nathan A et al. “Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States.”The American journal of sports medicine 42,10 (2014): 2363-70. doi:10.1177/0363546514542796

- Spindler, Kurt P, and Rick W Wright. “Clinical practice. Anterior cruciate ligament tear.”The New England journal of medicine 359,20 (2008): 2135-42. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0804745

- Murray, Martha M et al. “The Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair (BEAR) Procedure: An Early Feasibility Cohort Study.”Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 4,11 2325967116672176. 21 Nov. 2016, doi:10.1177/2325967116672176

- Barnett, Samuel C et al. “Earlier Resolution of Symptoms and Return of Function After Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair as Compared with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction.”Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 9,11 23259671211052530. 9 Nov. 2021, doi:10.1177/23259671211052530

- Saithna, Adnan et al. “Combined ACL and Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction.”JBJS essential surgical techniques 8,1 e2. 10 Jan. 2018, doi:10.2106/JBJS.ST.17.00045

Biography: Cody McGrale is currently a second-year medical student at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.